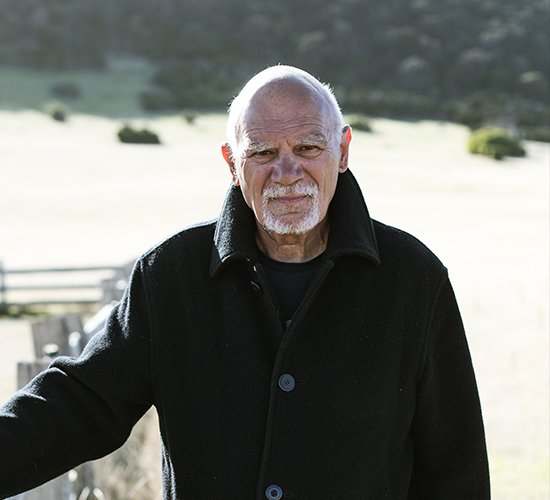

Rodney Gibbins

"No matter what happens we cannot undo the past. But to have the broader Tasmanian community stand with us to recognise us for who we are, to recognise our rights and aspirations – wouldn’t that be something."

"Our story, the story of the Tasmanian Aboriginal community has been one of struggle and denial. But despite the many obstacles put in front of us we have survived and prospered."

“We can look at my early life, which was one of extreme racism.

We were frowned upon by the white community and put into disadvantaged suburbs around Launceston in Northern Tasmania. We were with other Cape Barren Island families, which was good for me growing up. But you were treated differently. I can remember being chased home after school almost every day during primary school. If they caught us we were bashed. These non-Aboriginal kids thought it was just mucking around, fun, their right. We were less than third-class citizens in our own country. Our parents, in this era, weren’t politically minded.

Let’s think about the term that is used often: reconciliation. It was the white man who took away my country, my culture, my language, my family. I don’t have anything to reconcile, other than pain and loss felt by the entire Aboriginal community. They [white people] should reconcile to the past wrongs committed against the Aboriginal community, stand with us to right those wrongs.

No matter what happens we cannot undo the past. But to have the broader Tasmanian community stand with us to recognise us for who we are, to recognise our rights and aspirations – wouldn’t that be something.

When I got involved in Aboriginal community politics in Tasmania it was the late 1970s. It was about fighting very strongly in those days for recognition, just personal identification as an Aboriginal person in Tasmania. It came from strong Aboriginal families. That went on for years before Governments and others finally relented and expressed an understanding and knowledge that there were Aborigines in this state.

As time marched on there was a growing political and social movement developing in the Aboriginal community that demanded recognition, acceptance, and autonomy to make its own decisions. The community gained a lot more confidence in itself and further developed the skills and abilities and power to progress their arguments.

I believe that this has been one of our greatest achievements as a community.

This led, finally, to such things as the return of the Crowther Collection. In my view, this would have been our first major political victory. But even then it was reluctant victory, reluctantly given up by the museum and by Government.

We took the remains of those 42 old men and women and ceremonially cremated them. In our view, their spirits were finally released, set free. But it had been a long tough haul, a hard slog.

The current generation of non-Aboriginal people can say, 'We weren’t there. We aren’t responsible for those wrongs.' No, you weren’t there. However, in part you are still responsible for the ongoing devastation and disadvantage that the Aboriginal community face today.

This is what we must look at. How do we overcome that?

There certainly are examples of behaviour that show the way forward. When there has been a personal commitment by our political and bureaucratic and community leaders there has been a positive response by the broader Tasmanian community.

This certainly happened in 1995 when then-Premier Ray Groom introduced Land Rights legislation to Parliament.

This resulted in the first and most significant land hand-back to the Aboriginal Community in this State culminating in 12 areas of land being returned to the Aboriginal community.

Within a few years Wybalenna, Cape Barron Island and Clarke Island were also returned. But that was 16 years ago.

Since then I fear that successive Governments have continued to erode the advances made by the Aboriginal community by eating away at Aboriginal influence and knowledge. But there are examples of where individuals and organisations are progressing those ideals of equality, justice, and recognition for the Aboriginal community.

The Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery apology, for their past practices of taking Aboriginal bodies, is a good example of that and where we should be all heading. A heartfelt apology is not the be-all and end-all of anything, particularly with our kind of history, but it is a promising pointer to the future, that they would be more willing to talk to us and the community about returning artifacts. It is a recognition that there were wrongs and they have to be held accountable for them.

This shows a way that government and other organisations as well as the broader community can look at in the future, about gaining the trust of the Aboriginal community as a whole. We don’t care about status and power in the white man’s world, that’s not our world… we prefer to expand and defend our own world, which is Aboriginal identity and culture.

I believe Aboriginal people are entitled to practice language and culture, to be personally identified and proud to be palawa/pakana in this State.

It is not a takeover. It is not at any cost to non-Aboriginal people. But we think it will lead to a better understanding between all people in the state.

Our story, the story of the Tasmanian Aboriginal community has been one of struggle and denial. But despite the many obstacles put in front of us we have survived and prospered. We will continue our quest for equality, justice, and recognition, as a community and as Aborigines."

Wybalenna

“Wybalenna is a very important place for our community. It is a brutal reminder of what the invasion of our country and colonisation has meant for our people.

Wybalenna is the place where George Augustus Robinson took our people, telling them that if they went with him, one day they would be free to return to their traditional lands.

Sadly, this was never to be.

The treatment our people received at Wybalenna and the poor conditions they were forced to live in only served to make many people sick. As a result of getting sick many of our people died at Wybalenna. The Aborigines who died at Wybalenna were buried there. Those who survived were taken to live in squalid conditions at putalina.

At Wybalenna George Augustus Robinson tried to ‘civilise and Christianise’ our people. Wybalenna was a place where racist and overseers attempted to destroy our culture, our traditions and our language.

They never succeeded.

Tasmanian Aboriginal culture continues to be strong and vibrant. Today, we continue to know our culture, practice our traditions and speak our language. We continue to stand strong on our land.”

(Wybalenna: Healthy Country Plan, 2015. Tasmanian Aboriginal Centre Inc.)

Wybalenna is situated on Flinders Island, North East Tasmania and is part of the Furneaux Archipelago as is Cape Barren Island.

Rodney Gibbins is one of 18 Tasmanians featured in our short film about the Tasmanian story. Rodney’s scene was filmed at wybalenna, Flinders Island.

Read about more Tasmanians

Carleeta Thomas

Rodney Croome